Physical signs

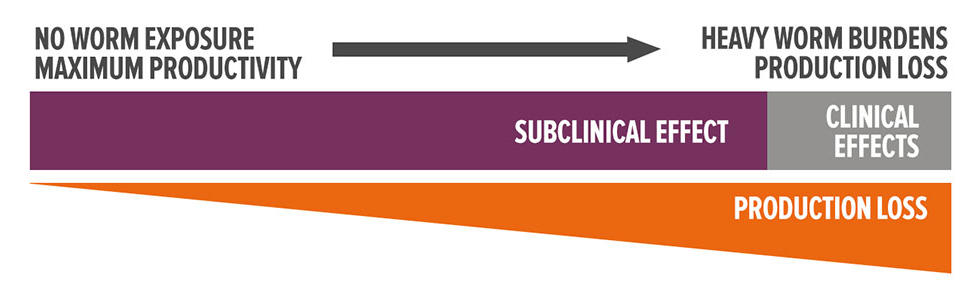

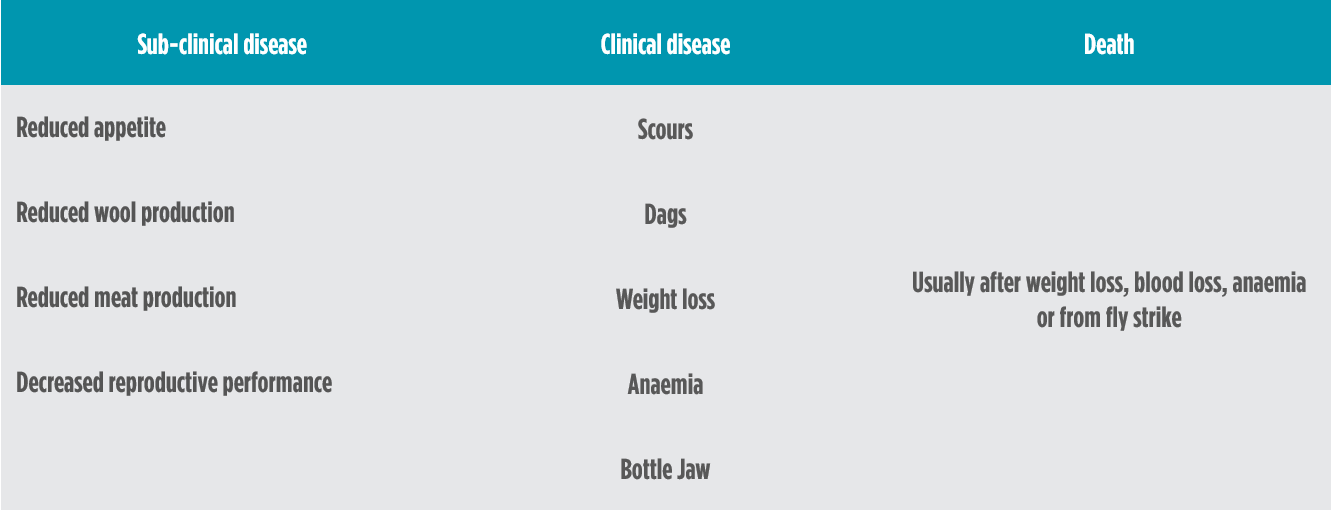

Almost all grazing animals have internal parasites. They often don’t cause clinical disease and stock can look normal or even in good condition. However, if animals ingest large numbers of worm larvae and infections get out of control, they can suffer from both subclinical disease (signs that can be measured but not seen visually) or clinical disease (e.g., scours, weight loss or even death).

Factors such as animal species, age, farming systems, pasture availability, and seasonality all contribute to the varying impacts of parasites on livestock.

A sheep with a zero worm burden has no compromise to its production, wool, lamb or meat as a result. There is an impact on production from the lowest worm burden through reduced appetite, refocus of immune system to the parasite, damage to the gastrointestinal system and potential protein and blood loss.

The visual effects (clinical signs) are apparent when the worm burden becomes high and there is substantial reduction in production and a negative impact on the health of the animal. It is the non-visual (sub-clinical) effects which accounts for the majority of production loss in a sheep enterprise as it can go un-noticed over a long period of time.